- Home

- Anna Roberts

Full Fathom Five (The Keys Trilogy Book 3)

Full Fathom Five (The Keys Trilogy Book 3) Read online

Copyright © 2016 by Anna Roberts.

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Cover photography licensed by Shutterstock.

Full Fathom Five

Book Three of The Keys Trilogy

by

Anna Roberts

Full Fathom Five

Part One

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part Two

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Epilogue

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Hark! Now I hear them, ding-dong, bell.

The Tempest Act I, scene II

Prologue

The first was a high school football player named Andrew Mackie. He was just seventeen, you know what I mean, and she was sure the way he looked must have been way beyond compare. But only because he was among the first; once they started piling up there must have been all kinds of interesting comparisons to be made. The depth of a hip socket, the size of a liver, the length of a long bone. She’d heard doctors tell of how the inside of a person is as unique as the outside.

Lupe Gonzalez came next, a pious mother of four crying, dark-eyed children. Then, like he’d got some ecclesiastical bug from unlucky Lupe and her sacred heart medals, he moved on to Sandra Dean, a sixty-two year old church deacon. No pattern, no bodies. One white teenage boy, one thirtysomething Latina and one old black lady.

She knew he did that on purpose. Never had any time for those ego-driven teratologists that clogged up police departments, those hopeless nitwits who thought you could tell a killer’s shoe-size, Mommy issues and other major malfunctions simply by ripping a page or two out of Silence of the Lambs. Profile schmofile. Hollywood nonsense.

“Tell me again,” she said, and Coronado hesitated. Poor man had never expected to deliver this news naked, but there it was. A woman could only live so long with the ripe, twitchy stink of teenage boys before a grown man started to smell like heaven to her. And Harry Coronado had always smelled good, like clean sweat and sugar and the limes he squeezed with his bare hands whenever he made mojitos.

He frowned. “Gloria, are you okay?”

He regretted it. They always did. Even though they’d been dancing around it since about 1992. Or maybe he regretted it because he didn’t do it eight years ago, when her boobs just about stayed up on their own.

“I’m fine,” she said. “I guess I just don’t believe a word of it.”

Harry sighed, his breath creasing her left nipple, but it was gone. What she’d mistaken for simple lust had been more complicated, the scramble of a man desperate to mitigate the worst news that anyone can ever deliver to a woman.

“I got it from Charlie,” he said. “Who was there. Trust me. You don’t need the details.”

“I do.”

“Gloria...”

She sat up on the mattress and reached for her cigarettes on the nightstand. “Don’t you tell me what I need and what I don’t need, Harry Coronado. I brought him into this goddamn world. Don’t you think I deserve to know how he left it?”

Harry looked as though he doubted whether anyone deserved that, but he told her anyway, the tale of a gruesome feast yanked straight out of the pages of Titus Andronicus. If it had been anyone but Lyle Raines responsible she would have said that was where it came from, but she doubted Lyle could even spell Titus Andronicus, let alone tell you the plot.

“He’s full of shit,” she said, stubbing out her smoke. “Never happened that way.”

Harry got that awful, pitying look in his eye. “I know you don’t want to believe it –”

“– it’s not a question of believing,” said Gloria. “It’s about knowing. How about Charlie? How much does he know?”

“Not everything. Not that.”

“Good. Don’t you dare tell him.”

Harry pressed a hand to his heart with as much dignity as if he’d been fully dressed. “I’m insulted that you think I would even dream of it. It’s not my place.”

“Sorry. I’m meaner than usual lately. Hormones, I guess.”

His glance turned wary, the way a man’s always did when confronted with the mysterious workings of the female body. He was trying so hard, but his eyes moved inevitably to the scar slashed above her bush – where she hadn’t even had time to pluck out the white hairs.

“They left the ovaries,” she said. “God, don’t they tell men anything?”

“It’s not bad. You kept your figure.”

“For now,” she said, reaching for another smoke. Fucking thing had gone berserk on her in her late thirties, sprouting growths that felt like tennis balls under the skin when she lay flat and ran a hand over her belly. Then there was the bleeding and the cramps, like the more it slid towards obsolescence the more her wretched uterus demanded attention, like that crazy old diva in Sunset Boulevard. Yeah, you’re ready for your close-up, you gnarled fibroid bitch. In a medical waste bucket. So long, and thanks for the monster baby.

The ceiling fan creaked above her, its slow blunt blades doing nothing more than stirring the sticky air like it was a pan of soup. She sucked down a lungful but it tasted just the same. Nothing to suggest that Lyle Raines had broken the habit of a lifetime and started telling the truth.

“If Charlie knew...” she said. “Jesus, I hate to think what that boy would do. Hothead, that one. You heard about him running off to do God knows what to his uncle?”

Harry ran a hand down her spine. “You can’t blame the kid. That was a terrible thing that happened to his mother.”

“It was, but Charlie’s got an unholy knack of taking terrible things and making them...I don’t know...terribler. Is that even a word?” She lay back on the mattress, seeking the security of small talk before Harry got back to feeling sorry for her. “What about you, anyway? That daughter of yours still giving you trouble?”

“Alexis? Yeah. She’s got religion now. The shiny-face, shiny-suit preacher kind. The kind that’s always hard up for cash.”

“Oh boy. Those nitwits?”

“Yep. She goes twice every Sunday to talk gibberish, go into a trance and fall the fuck over because the Holy Spirit crawled up her ass or something. I don’t know where I went wrong with that girl; she was raised a good Catholic.”

“No such thing as a good Catholic,” said Gloria. “We start from the premise that we’re all born bad.”

“Meh, it’s bullshit,” said Harry, reaching down to the floor to fish his wallet from his pants. “Nobody smart believes that. You only have to look at your kids and your grandbabies to see it’s something they made up to scare you. There’s nothing so shin

y and blameless as a newborn.”

“Amen,” she said, and some weird, wild mood swing lurched out of nowhere, stinging her eyes. She thought he’d missed it, but Harry swayed towards her, his bare shoulder bumping hers.

“Stop,” she said, taking the wallet. “I told you; I know he’s not dead.” She looked instead at the photo he had been meaning to show her, a brown little boy in a red bathing suit, eyes scrunched against the sun and his grin baring a gap where his front teeth used to be. “This him?”

“Yeah. That’s Gabe. He goes by Gabe now. Poor kid got sick of being called Eggs.”

She smiled. “Benedict. Right. How’s that working out for him on the curse-busting front?”

Harry sighed. “So far so good, but he’s nine. I don’t hold out much hope. He might dodge the bullet if it was just his dad was a werewolf, but with me in the mix...well, you know how it skips generations like that.”

Gloria handed him back the wallet. “Well,” she said. “You know where I am if you need me.”

He would. They always did; people said karma was a bitch but she had nothing on heredity. After he had said their awkward goodbyes (and that’s why I never banged him sooner) she walked alone through the quiet house and empty yard, trying to taste Yael on the wind and the dust motes.

Big now. He had grown over the years, like a tiny puppy that follows you home one day and grows to the size of a small sofa. A small sofa with a row of teeth at one end and an overactive asshole at the other, shitting all over everything and making you clean up after it. No, that wasn’t right. Not grown. Swelled. He had got puffed and crazy, until he was so large he could blow in like the nervous salt breath that gusted in at the start of hurricane season, or the barely contained panic that had rippled through the state back when Kennedy was president.

Eighteen. She’d been eighteen during the Cuban Missile Crisis. She had never expected to live this long, but fifty-five felt old as balls. Forty-two of those years had been spent with Yael in one form or another. A long time to cultivate a grudge.

The hens cackled and scattered in front of her feet as she walked across the yard. Dumb things, but smart enough to fall silent when Yael was around. Maybe on some dipshit chickeny level they remembered the time when he got experimental with the birds, trying to get inside their heads and walk around in their bodies, just to see what it felt like.

Sonofabitch had dropped half her flock. Some died right away. Others walked like wind-up toys for a few steps before blood came pouring from their eyes and mouth and they died, gurgling in panic.

But today they were normal. The usual idiot shit-factories, gobbling and pooping all over the place. She scooped up the nearest bird, holding its wings closed against its body to keep it from flapping. It sat docile in her arms, stringy legs hanging down and empty head bobbing in a dumb attempt to figure out why the scenery had just changed.

“Good girl,” she said, stroking the smooth, dust-smelling feathers. Poor things felt like air in your hands if you pressed even gently, hard enough to feel the dinner-sized body under the puffed shell of plumage.

She shifted her grip, holding the bird upside by the feet. With her other hand she reached for the ax, already humming to herself. Death was nothing unusual. Death was older than anything. Human, chicken, tubeworm – didn’t matter. Old as the fabric of the universe. You couldn’t disturb it with just death, because death was only a part of it. You had to know how to poke between the holes in the weave, and that was something you either could do or couldn’t, like rolling your tongue up at the sides or being able to stand the taste of cilantro.

Gloria set the chicken on the block. She brought up the ax just long enough to feel the weight of it and remember how once she had felt the brief, fizzy panic of hesitation, but not now. Intent was everything. If you meant it you stood a better chance of making that hole.

She cut off the head with one blow. The body twitched and fluttered and the eyes and beak still moved, but she was singing now, the tune in her head pouring out of her mouth...

...and there he spied a bonnie lass, a windae peepin’ through,

Oh Charlie is my darling, my darling, my darling

Charlie is my darling, the young chevalier.

He loved music. He loved flesh and blood. If he was out there she could call him, and if she could call him then it was all true and West really was dead, served up in sausage links by that asshole Lyle Raines.

Gloria dabbled her fingers in the warm blood and touched them to her lips. The wrong, vital taste of it on the tip of her tongue gave her purpose, allowed her to poke that mental gimlet deeper into the universe, seeking her son.

Harry was wrong. It wasn’t a mother refusing to believe her child was dead. It was a witch knowing that he wasn’t. Yael had fought and lied and tricked and conned his way into that deal, and the only way he was ever going to give it up was if West was dead and rotting and no good to him any more.

Nothing.

She stopped singing and listened, but the hens – briefly silenced by the thump of the ax – started to cluck once again. The breeze stirred the palm fronds nearby, but the air smelled only of rot and salt and life and sweat, the way it always did in South Florida.

Still nothing. Lyle Raines was full of shit.

1

Charlie had seen more than his fair share of dead people over the years, but never quite like this before. The light was cold and gray and buzzed at a pitch that human ears might miss, but to him sounded like the drone of a trapped, dying bee. The cooled air was so harsh with antiseptic and preservatives that the underlying sweetness of death seemed almost pleasant; at least rot was natural.

They had arranged her carefully on the table so that the back of her head was mostly hidden with a foam pillow, although when they had first drawn back the sheet he could have sworn he saw darkness behind her right ear. He had quickly moved round to her left.

She looked like a waxwork, white and still, the sheet pulled up to her chin. Her lips looked more sunken than usual and he wondered how many of her remaining teeth she had blown out when she did it. He swayed for a moment, the whole room blurring into one big pale gray nothing, his stomach doing backflips. Somehow it was worse when they cleaned them up, hid the holes, left the gory details to your imagination. At least when it was all splattered out there in front of you - bowels and bile and bone splinters – you knew there was nowhere to hide from the horror. You got it all over with in one go.

Thank God that little shit Gabe wasn’t here. Charlie didn’t think he could go through all that Catholic open-casket bullshit, where they dressed the dead up like dummies and invited every drunk uncle from the far corners of the family tree to come and gawk at the body.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s her.”

“I’m sorry,” said the doctor, or coroner, or police surgeon or whatever the hell he was. Charlie had always been self-aware enough to know that his own ego had never exactly been modest, but he had never felt quite so small as he did right now in the glaring light of officialdom. Like one of those skittering, circling insects that freak out when you lift the corner of some damp, smelly piece of old cardboard.

“Excuse me,” he said, needing to get the hell away from Gloria’s body. “I need some water or something.”

He staggered out into the hall. The dirty-cream colored doors swung shut behind him, closing off what he didn’t want to see. It could have been worse, he told himself. It could have been Eli, and holy shit that would have been a whole fresh hell-can of diseased and inbred worms. He was still trying to get his head around how easily Ruby had dealt with that. Not to mention what that had said about her.

“You know, there are more efficient ways...” she’d said, working too easily through sinew and cartilage with Charlie’s good knife.

Efficient. Goddamn swamp wolves. He thought he might have hit her then, if he hadn’t been sure it wouldn’t make him feel worse. Or that a little part of him was still hopeful that she was telling th

e truth about being pregnant.

A new guy came into the hall. This one was definitely a cop, Cubano probably, judging by the perfect suit and shiny hair. They always acted like they had everything to prove.

“Detective Fernando,” he said, flashing his badge. His fingernails were pinker and shinier than those of some girls. Ruby in particular. She’d still had a thin rinds of dried blood under her nails, the kind of thing you had to grow out because no scrub brush could ever get that deep. Charlie thought about DNA and tried not to.

“I know this is a difficult time...”

“Yeah. No shit.”

“Mr. Silver, if you could just tell us the last time you saw Eli Keane –”

“– he didn’t do this, Detective,” said Charlie. “There is no goddamn way he did this. He loved Gloria. He would never have done anything in the world to hurt her. Besides, didn’t she leave a note?”

“Right, the note,” said Fernando. “I haven’t been able to get anywhere with that.”

“Oh?”

“She mentioned someone named Yael. Do you know who she might be referring to?”

There was no way out of this one, so he dived right in. “Yael is the name she gave to a ghost she thought was haunting her house,” said Charlie, and right away Fernando’s face softened into that blank look of appalled sympathy that people got whenever grandma said something weird or was rounded up wandering the marina in her underwear.

“Right,” he said. “The Alzheimer’s?”

“Yeah. It got pretty bad. She’d have these lucid moments, and I guess one of them was when she decided to...you know. I mean, wouldn’t you? ‘Cause I fucking would. I can’t imagine anything worse.”

Fernando nodded. “I know. It’s tragic. A terrible thing. I’m afraid it’s just procedure, but we do have to ask about Eli Keane –”

“– sure, right,” said Charlie. “And no. I haven’t seen him for days. Thursday, maybe. I don’t know. Maybe he’s shacked up somewhere. Incommunicado, you know? He always did have an eye for the ladies.”

Fifty Shades Fatter - A Sequel (Fifty Shades of Neigh Book 2)

Fifty Shades Fatter - A Sequel (Fifty Shades of Neigh Book 2) Full Fathom Five (The Keys Trilogy Book 3)

Full Fathom Five (The Keys Trilogy Book 3) Isle of Spirits (Keys Trilogy Book 2)

Isle of Spirits (Keys Trilogy Book 2) The Wolf Witch (The Keys Trilogy Book 1)

The Wolf Witch (The Keys Trilogy Book 1) Fifty Shades of Neigh - A parody

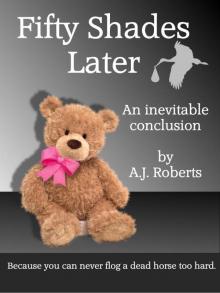

Fifty Shades of Neigh - A parody Fifty Shades Later: An Inevitable Conclusion (Fifty Shades of Neigh Book 3)

Fifty Shades Later: An Inevitable Conclusion (Fifty Shades of Neigh Book 3)